In recent years, the sustainability question in Africa’s civil society sector has moved from an afterthought to an alarm bell. Once comfortably reliant on the pipelines of international donor funding, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) across the continent particularly in Nigeria and West Africa are increasingly grappling with the reality of diminishing grants, shifting priorities, and the unsettling volatility of global aid.

As donor fatigue sets in and international funding streams become more transactional, competitive, and politically contingent, CSOs are confronting a hard truth: survival now depends less on who funds you and more on how well you fund yourself.

The stakes are no longer abstract. According to the West Africa Civil Society Institute (WACSI), financial instability remains one of the most pressing challenges facing CSOs in the region, with many operating on short-term grants and lacking reserves for future planning. This is not simply a fiscal problem; it is a structural crisis with implications for civic space, democratic accountability, and grassroots development.

The era for grants dependency is over; Grants have long been the lifeblood of African CSOs. But overreliance has fostered a dangerous cycle: mission drift, donor appeasement, short-term programming, and institutional fragility. Far too many organizations restructure not based on local and beneficiaries needs, but based on the whims of funding cycles. Vision is repeatedly sacrificed at the altar of proposal templates.

The consequences are profound. Grassroots voices are diluted. Projects are fragmented. And long-term impact gives way to metrics that appease donor dashboards but rarely transform lives or lasting impact on the sector. The result is a civil society sector that often operates in survival mode, technically sound, but financially brittle.

The MacArthur Foundation, for instance, concluded its ‘On Nigeria’ anti-corruption initiative in 2024, signaling a significant strategic shift despite assurances of continued support through final grants and institutional strengthening efforts. Similarly, USAID’s programming in Nigeria faced renewed scrutiny and potential downsizing in early 2025, driven by the aftermath of Trump administration’s foreign policy disruptions and realignments in international development priorities. CSO’s now need to reflect on creating lasting impact and shifts in policies and reforms, and we must do so by learning to work with partners beyond ourselves, understanding that power dynamics leveraging on influence structures. This will be the new dependance.. each other.

From Talking Point to Survival Strategy

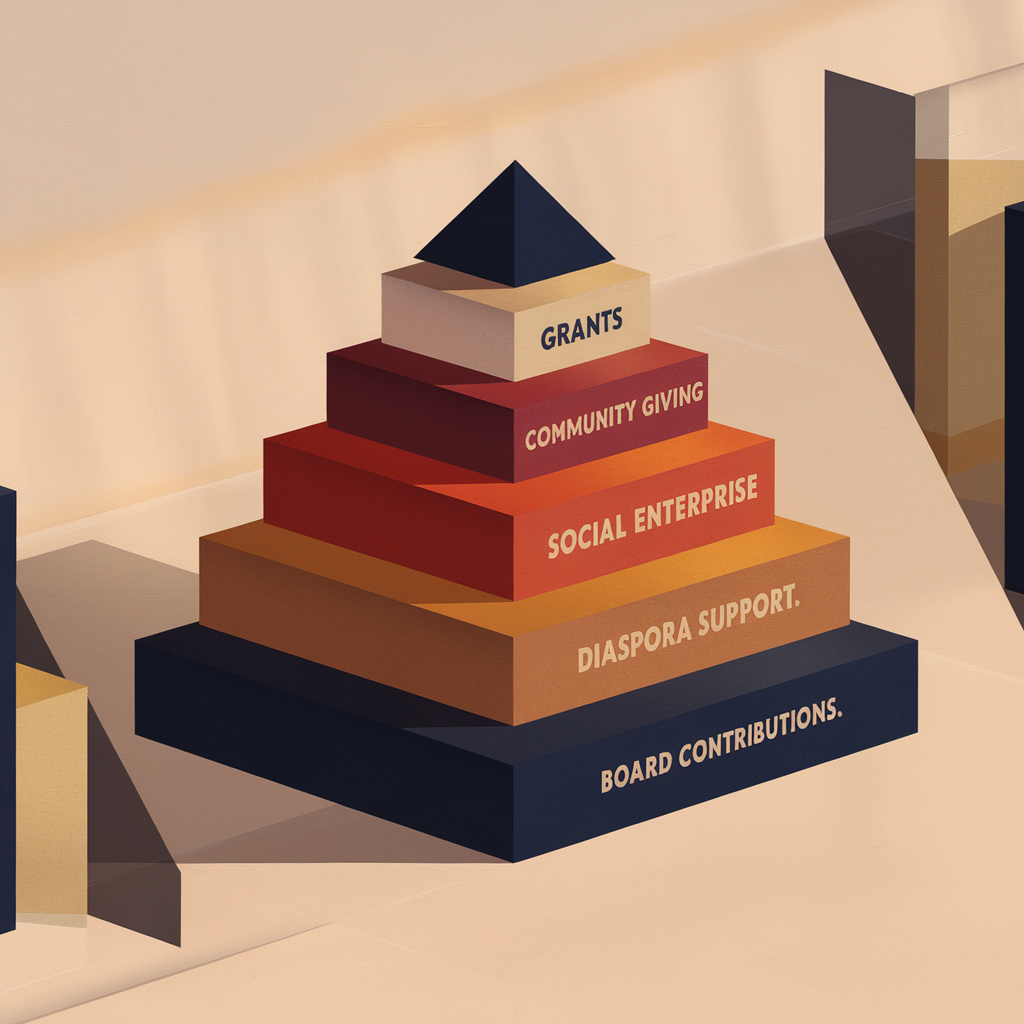

The call to diversify funding is not new, but it is no longer optional. To remain resilient, CSOs must reimagine themselves as value-creating institutions capable not just of absorbing grants, but of generating, sustaining, and scaling their own revenue ecosystems.

This doesn’t mean a wholesale abandonment of grants. It means a bolder, broader, and better-balanced approach that weaves alternative streams into the organization’s DNA.

Some promising models include:

-Social enterprises that offer services (e.g., training, consulting, media, agriculture) whose profits support advocacy or community programs.

-Community-based fundraising, including digital crowdfunding, monthly giving programs, and donor circles.

-Diaspora engagement, tapping into remittance-rich networks eager to support trusted, transparent local causes.

-Fee-for-service models such as research partnerships, event hosting, or thematic convenings with paying partners.

These are not silver bullets. Each comes with trade-offs in time, capacity, and alignment. But collectively, they represent a path forward; one rooted in intentionality, creativity, and independence.

The Myth of ‘Local’ Philanthropy

An often overlooked dimension of funding diversification is the character of local giving itself. In many African countries, philanthropic support is informal, tied to personalities, or rooted in religious and ethnic loyalties. This creates a tension: can CSOs secure local support without sacrificing their autonomy?

It is here that transparency becomes not just a virtue, but a protective mechanism. The ability to clearly communicate who supports you and why it’s essential to retaining public trust. So too is the skill of navigating complex social landscapes, where elite donors may offer generous funding but come with expectations that blur lines between civic engagement and political patronage.

In truth, the challenge isn’t just about finding local funders, it’s about cultivating local stakeholders. This is a deeper, more demanding task that calls for storytelling, trust-building, and long-term community presence. i.e. CSO’s can design more robust and strategic program initiatives that engage the private sector and businesses with corporate social responsibility (CSR) budgets moving beyond the traditional focus on boreholes, school WASH programs, traffic light donations, or occasional charity visits. By aligning CSR with systemic and locally relevant development needs, CSOs can position themselves as partners in delivering sustainable impact.

No diversification strategy is sustainable without the active involvement of the board. Yet in many CSOs, boards remain ceremonial, appearing for annual reports, but absent from the organization’s financial engine.

That must change.

Boards should be leveraged not only for governance but for strategic networking, fundraising, and resource mobilization. Members must be selected not just for their titles, but for their ability to connect the organization to funding pathways both domestic and international. Governance, in this new reality, includes the capacity to build financial resilience.

What does financial resilience and sustainability really mean? Too often, “sustainability” is reduced to a fundraising buzzword, something to be tacked onto proposals or inserted into strategy documents. But at its heart, sustainability is about freedom: the freedom to set your agenda, the freedom to innovate, the freedom to say “no” when projects misalign with purpose.

Communications professionals within CSOs have a unique role in shaping this narrative. They must push back against the scarcity mindset and begin telling stories of agency, resilience, and impact. Not in abstract terms, but with tangible evidence that self-determined organizations are more accountable, more trusted, and more durable.

At Thoughts and Mace Advisory, we’ve seen this play out in real-time . As we support CSOs across West Africa from frontline advocacy groups to policy think tanks, the ones that thrive are those that invest in governance, strategy, and financial literacy. They ask the right questions: What value do we offer? Who would pay for it? How do we balance revenue with mission?

They also explore safe, low-risk financial instruments that allow them to preserve grant capital while generating returns. One such tool is a fixed deposit account, where a portion of long-term project funds can be invested for up to one year, provided those funds are not required for immediate implementation. This strategy is especially viable for projects with delayed timelines or those spanning multiple years.

In Nigeria and other West African countries, fixed deposit interest rates can offer modest but valuable returns. However, it is crucial that any interest earned is transparently recorded and reported to donors and relevant regulatory bodies. According to the law and best financial practice, such proceeds must be reinvested into project implementation and legitimate operational costs such as staff salaries not diverted or privately used. This approach not only stretches donor funds further but signals strong financial stewardship which is an essential trait for winning trust and attracting future funding.

SO, ultimately, funding diversification is a journey, not a destination. It takes trial and error, honest audits, and a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths.

In conclusion: The future of civil society in West Africa and indeed across much of the continent will not be written in donor memos, reports and even policy briefs. It will be shaped by the organizational decisions we make today: to diversify, to innovate, to own our stories, and to define sustainability on our own terms.

In a season where uncertainty is the only constant, CSOs must not merely survive; they must lead, adapt, and build.

West Africa Civil Society Institute (WACSI). (2021). The State of Civil Society in West Africa: Strengthening CSOs Beyond Aid.

https://wacsi.org/publication/the-state-of-civil-society-in-west-africa